Vectors and Vectors Operations With JavaScript

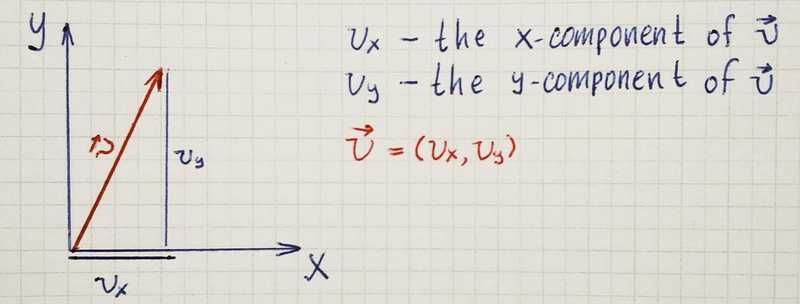

Vectors are the precise way to describe directions in space. They are built from numbers, which form the components of the vector. In the picture below, you can see the vector in two-dimensional space that consists of two components. In the case of a three-dimensional space vector will consists of three components.

We can write class for vector in 2D and call it Vector2D and then write one for 3D space and call it Vector3D, but what if we face a problem where vectors represent not a direction in the physical space. For example, we may need to represent color(RGBA) as a vector, that will have four components — red, green, blue and alpha channel. Or, let’s say we have a vector that gives fractions of proportions out of n choices, for example, the vector that describes the probability of each out five horses winning the race. So we make a class that not bound to dimensions and use it like this:

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

}

const direction2d = new Vector(1, 2)

const direction3d = new Vector(1, 2, 3)

const color = new Vector(0.5, 0.4, 0.7, 0.15)

const probabilities = new Vector(0.1, 0.3, 0.15, 0.25, 0.2)Vector Operations

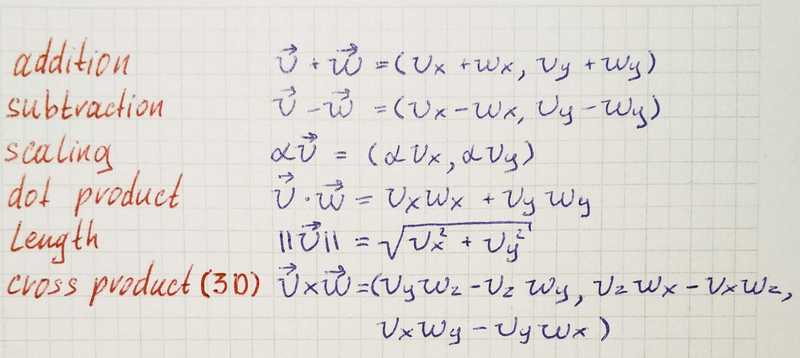

Consider two vectors, and assume that α ∈ R is an arbitrary constant. The following operations are defined for these vectors:

In the repository alongside with library lives React project, where library we are building used to create visualizations. If you are interested in learning how these two-dimensional visualizations made with React and SVG, check out this part.

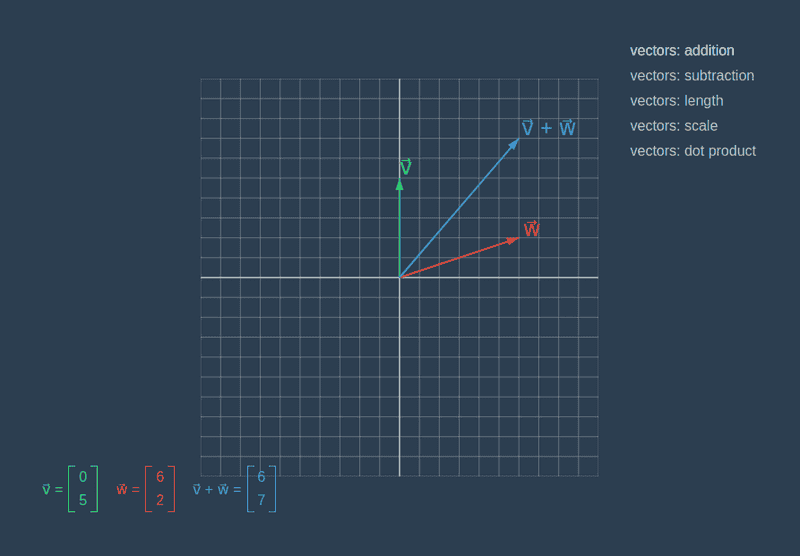

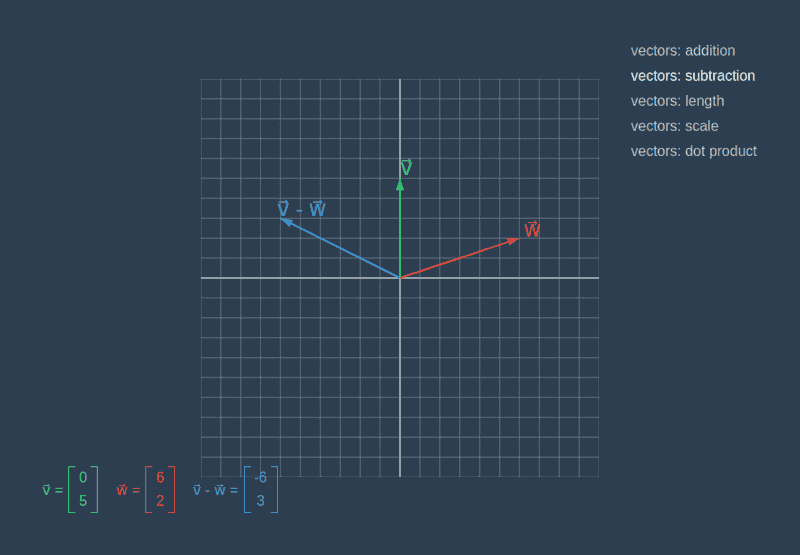

Addition and Subtraction

Just like numbers, you can add vectors and subtract them. Performing arithmetic calculations on vectors simply require carrying out arithmetic operations on their components.

Methods for addition receives other vector and return new vectors build from sums of corresponding components. In subtraction, we are doing the same but replace plus on minus.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

add({ components }) {

return new Vector(

...components.map((component, index) => this.components[index] + component)

)

}

subtract({ components }) {

return new Vector(

...components.map((component, index) => this.components[index] - component)

)

}

}

const one = new Vector(2, 3)

const other = new Vector(2, 1)

console.log(one.add(other))

// Vector { components: [ 4, 4 ] }

console.log(one.subtract(other))

// Vector { components: [ 0, 2 ] }Scaling

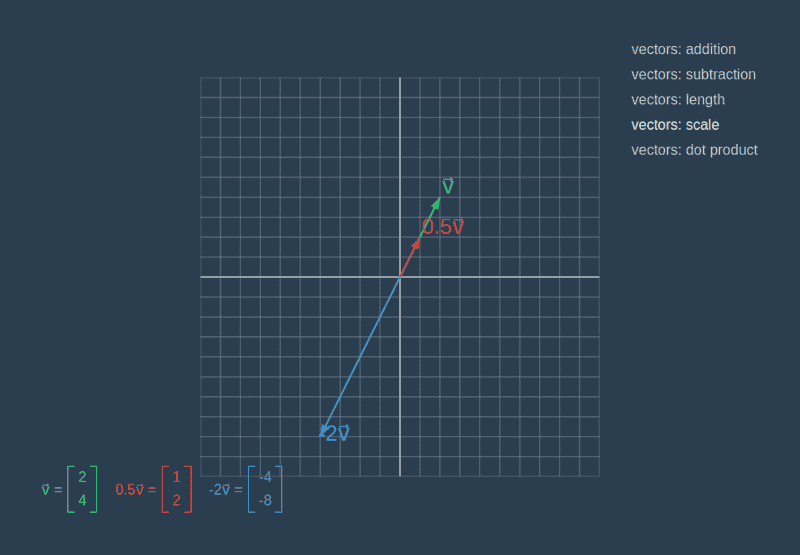

We can also scale a vector by any number α ∈ R, where each component is multiplied by the scaling factor α. If α > 1 the vector will get longer, and if 0 ≤ α < 1 then the vector will become shorter. If α is a negative number, the scaled vector will point in the opposite direction.

In scaleBy method, we return a new vector with all components multiplied by a number passed as a parameter.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

scaleBy(number) {

return new Vector(

...this.components.map(component => component * number)

)

}

}

const vector = new Vector(1, 2)

console.log(vector.scaleBy(2))

// Vector { components: [ 2, 4 ] }

console.log(vector.scaleBy(0.5))

// Vector { components: [ 0.5, 1 ] }

console.log(vector.scaleBy(-1))

// Vector { components: [ -1, -2 ] }Length

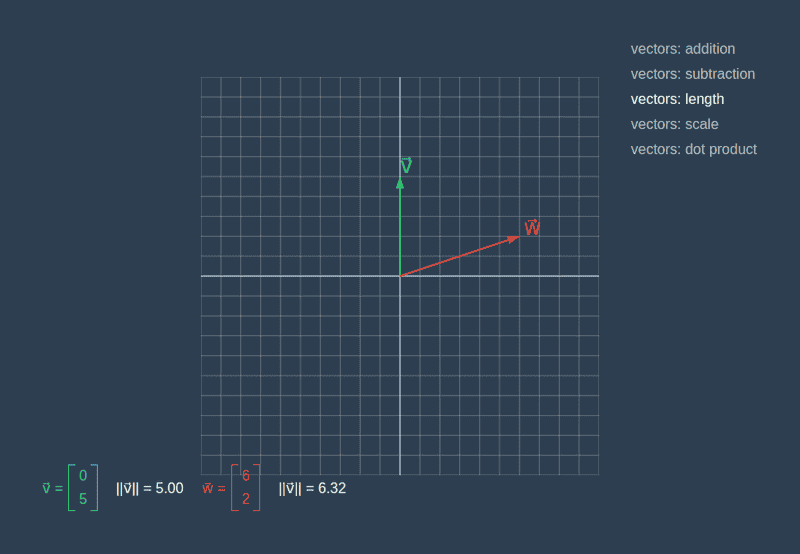

A vector length is obtained from Pythagoras’ theorem.

The length method is very simple since Math already has a function we need.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

length() {

return Math.hypot(...this.components)

}

}

const vector = new Vector(2, 3)

console.log(vector.length())

// 3.6055512754639896Dot Product

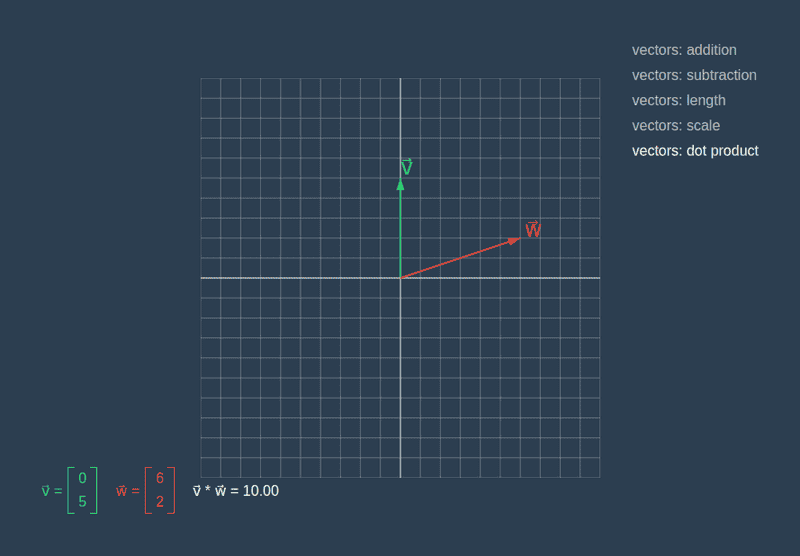

The dot product tells us how similar two vectors are to each other. It takes two vectors as input and produces a single number as an output. The dot product between two vectors is the sum of the products of corresponding components.

In the dotProduct method, we receive another vector as a parameter and via reduce method obtain the sum of the products of corresponding components.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

dotProduct({ components }) {

return components.reduce((acc, component, index) => acc + component * this.components[index], 0)

}

}

const one = new Vector(1, 4)

const other = new Vector(2, 2)

console.log(one.dotProduct(other))

// 10Before we look at how vectors directions relate to each other, we implement the method that will return a vector with length equal to one. Such vectors are useful in many contexts. When we want to specify a direction in space, we use a normalized vector in that direction.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

normalize() {

return this.scaleBy(1 / this.length())

}

}

const vector = new Vector(2, 4)

const normalized = vector.normalize()

console.log(normalized)

// Vector { components: [ 0.4472135954999579, 0.8944271909999159 ] }

console.log(normalized.length())

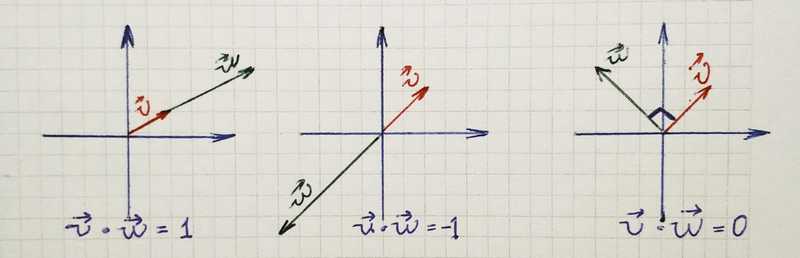

// 1If we take the dot product of two normalized vectors and the result is equal to one it means that they have the same direction. To compare two float numbers, we will use the areEqual function.

const EPSILON = 0.00000001

const areEqual = (one, other, epsilon = EPSILON) =>

Math.abs(one - other) < epsilon

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

haveSameDirectionWith(other) {

const dotProduct = this.normalize().dotProduct(other.normalize())

return areEqual(dotProduct, 1)

}

}

const one = new Vector(2, 4)

const other = new Vector(4, 8)

console.log(one.haveSameDirectionWith(other))

// trueIf we take the dot product of two normalized vectors and the result is equal to minus one it means that they have the exact opposite direction.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

haveOppositeDirectionTo(other) {

const dotProduct = this.normalize().dotProduct(other.normalize())

return areEqual(dotProduct, -1)

}

}

const one = new Vector(2, 4)

const other = new Vector(-4, -8)

console.log(one.haveOppositeDirectionTo(other))

// trueIf we take the dot product of two normalized vectors and the result is zero, it means that they are perpendicular.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

isPerpendicularTo(other) {

const dotProduct = this.normalize().dotProduct(other.normalize())

return areEqual(dotProduct, 0)

}

}

const one = new Vector(-2, 2)

const other = new Vector(2, 2)

console.log(one.isPerpendicularTo(other))

// trueCross Product

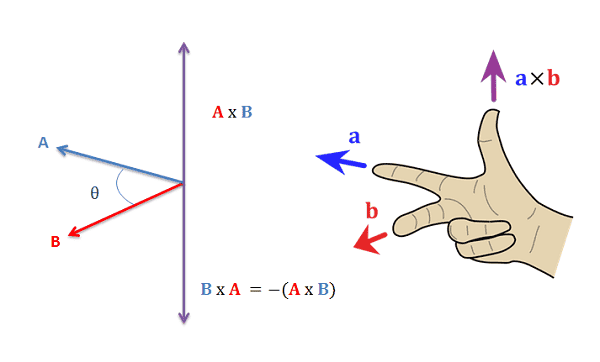

The cross product is only defined for three-dimensional vectors and produces a vector that is perpendicular to both input vectors.

In our implementation of the cross product, we assume that method used only for vectors in three-dimensional space.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

// 3D vectors only

crossProduct({ components }) {

return new Vector(

this.components[1] * components[2] - this.components[2] * components[1],

this.components[2] * components[0] - this.components[0] * components[2],

this.components[0] * components[1] - this.components[1] * components[0]

)

}

}

const one = new Vector(2, 1, 1)

const other = new Vector(1, 2, 2)

console.log(one.crossProduct(other))

// Vector { components: [ 0, -3, 3 ] }

console.log(other.crossProduct(one))

// Vector { components: [ 0, 3, -3 ] }Other useful methods

In real-life applications those methods will not be enough, for example, we may want to find an angle between two vectors, negate vector, or project one to another.

Before we proceed with those methods, we need to write two functions to convert an angle from radians to degrees and back.

const toDegrees = radians => (radians * 180) / Math.PI

const toRadians = degrees => (degrees * Math.PI) / 180Angle Between

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

angleBetween(other) {

return toDegrees(

Math.acos(

this.dotProduct(other) /

(this.length() * other.length())

)

)

}

}

const one = new Vector(0, 4)

const other = new Vector(4, 4)

console.log(one.angleBetween(other))

// 45.00000000000001Negate

To make a vector directing to the negative direction we need to scale it by minus one.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

negate() {

return this.scaleBy(-1)

}

}

const vector = new Vector(2, 2)

console.log(vector.negate())

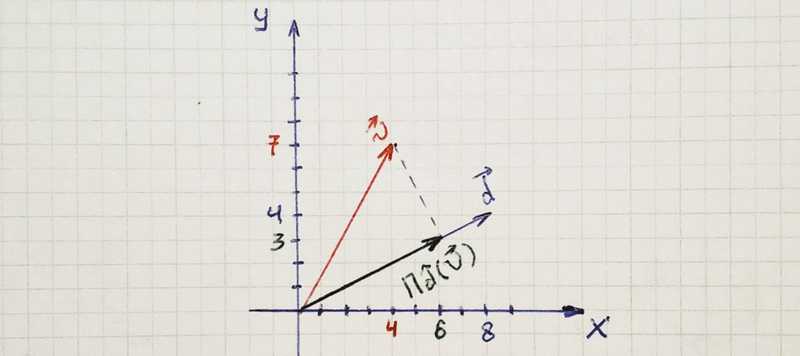

// Vector { components: [ -2, -2 ] }Project On

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

projectOn(other) {

const normalized = other.normalize()

return normalized.scaleBy(this.dotProduct(normalized))

}

}

const one = new Vector(8, 4)

const other = new Vector(4, 7)

console.log(other.projectOn(one))

// Vector { components: [ 6, 3 ] }With Length

Often we may need to make our vector a specific length.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

withLength(newLength) {

return this.normalize().scaleBy(newLength)

}

}

const one = new Vector(2, 3)

console.log(one.length())

// 3.6055512754639896

const modified = one.withLength(10)

// 10

console.log(modified.length())Equal To

To check if two vectors are equal we will use areEqual function for all components.

class Vector {

constructor(...components) {

this.components = components

}

// ...

equalTo({ components }) {

return components.every((component, index) => areEqual(component, this.components[index]))

}

}

const one = new Vector(1, 2)

const other = new Vector(1, 2)

console.log(one.equalTo(other))

// true

const another = new Vector(2, 1)

console.log(one.equalTo(another))

// falseUnit Vector and Basis

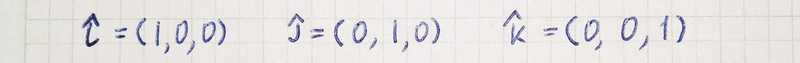

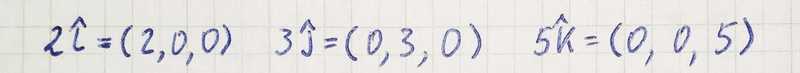

We can think of a vector as a command to “go a distance vx in the x-direction, a distance vy in the y-direction and vz in the z-direction.” To write this set of commands more explicitly, we can use multiples of the vectors* ̂i, ̂j,* and* ̂k*. These are the** unit vectors** pointing in the x, y, and z directions, respectively:

Any number multiplied by* ̂i *corresponds to a vector with that number in the first coordinate. For example:

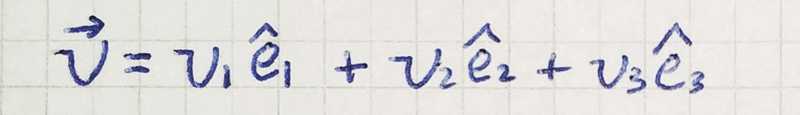

One of the most important concepts in the study of vectors is the concept of a basis. Consider the space of three-dimensional vectors ℝ³. A basis for ℝ³ is a set of vectors {ê₁, ê₂ , ê₃} which can be used as a coordinate system for ℝ³. If the set of vectors {ê₁, ê₂, ê₃} is a basis then we can represent any vector *v⃗∈ℝ³ *as coefficients (v₁, v₂, v₃) with respect to that basis:

The vector v⃗ is obtained by measuring out a distance v₁ in the ê₁ direction, a distance v₂ in the ê₂ direction, and a distance v₃ in the ê₃ direction.

A triplet of coefficients by itself does not mean anything unless we know the basis being used. A basis is required to convert mathematical objects like the triplet* (a, b, c)* into real-world ideas like colors, probabilities or locations.